Reflections on Ireland

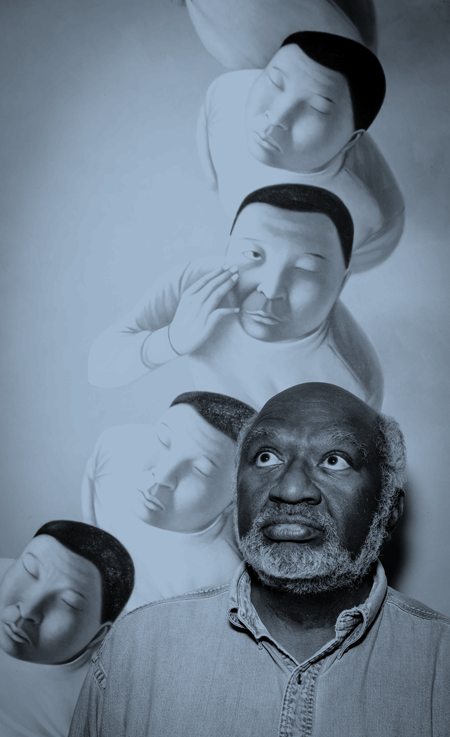

Photo: Charles Coe

I was in Dingle, Ireland recently to teach poetry in an American MFA program abroad. Some of my workshop sessions were held at An Diseart, an Irish spiritual and cultural center that shares the grounds with St. Mary’s Church. On those grounds is a tiny cemetery where lie the nuns who over the centuries have run the church convent.

Flying back to Boston, thirty-five-thousand feet over the Atlantic with two weeks in Ireland behind me, my thoughts kept drifting back to that cemetery, and to the time when the Catholic Church ruled the country with an iron hand. Church dogma dominated civic life; no Catholic politician would consider any action without knowing “his” (the Cardinal's) thoughts on the matter and making sure he approved.

But modern Ireland has broken those shackles: In 1985 it legalized birth control. In 1995 it revoked the constitutional prohibition against divorce. In 2015 it became the first country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage through a popular vote.

And then the most remarkable development of all: in June, Ireland elected Leo Varadkaran, an openly gay man with an Indian immigrant father and Irish mother, as “taoiseach” (prime minister). Later that month Mr. Varadkaran proudly led Dublin’s gay pride parade.

Today’s Ireland is one the Sisters of St. Mary’s of olden days would neither recognize nor condone. The world in which those women lived symbolizes the profound contradictions of Irish history—the mix of beauty and ugliness, the capacity for both gentle lyricism and stone-hearted cruelty. They spent their days in quiet contemplation, surrounded by the serene beauty of the green hills, floating like black-clad ghosts through the church corridors, secure in the rightness and beauty of their vocations.

But they were complicit in a system of rigid patriarchy and repressive moralism in which sexual abuse was endemic, physical violence against children was standard disciplinary practice and unwed mothers were virtually imprisoned to provide slave labor for the Church. It was a system whose deep wounds to the country's psyche are only beginning to heal.

The idea of modern Ireland, a country that could turn away from the Church’s “guidance,” would have been inconceivable to the Good Sisters of St. Mary’s. Inconceivable to those women for whom the Bishop’s word was the unquestioned word of God. Women, souls committed to their vision of Christ, whose mortal remains now lie shaded beneath the oaks.